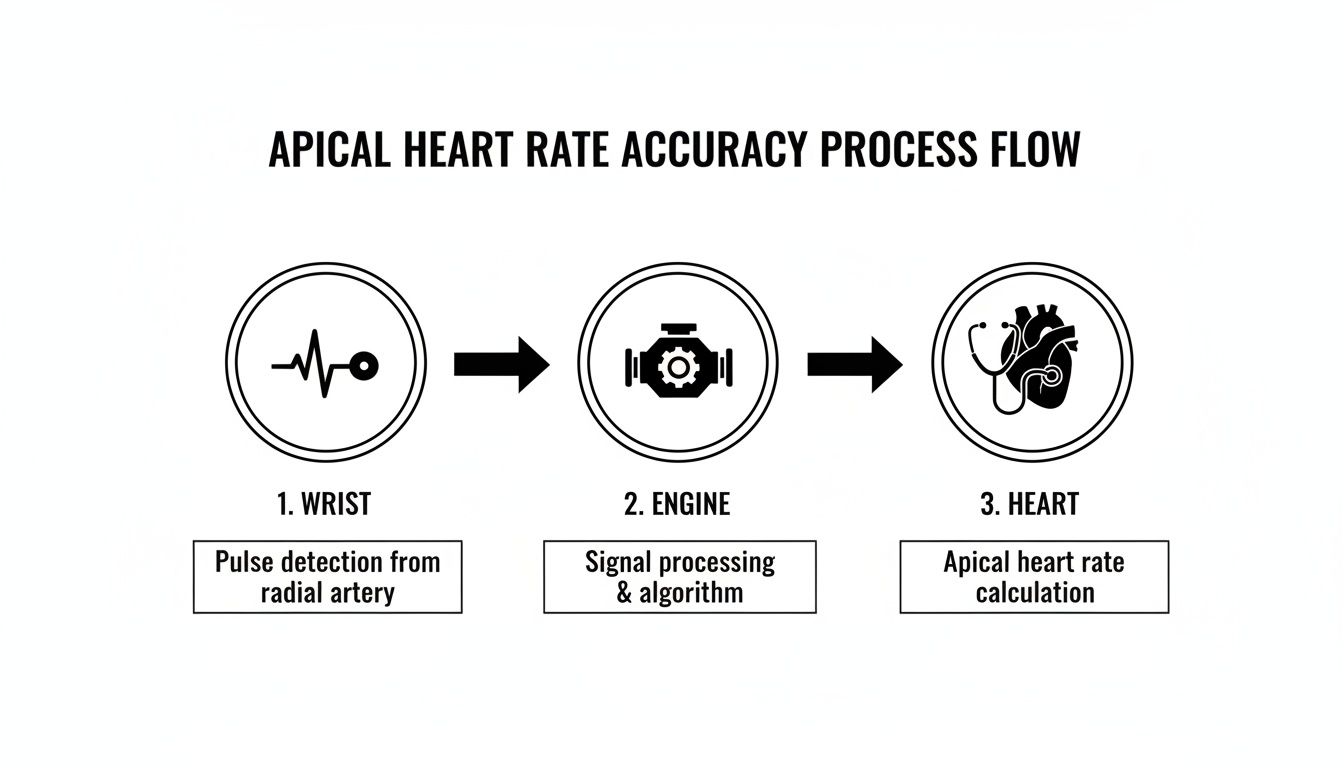

When you feel a pulse at your wrist, you’re feeling the ripple effect of your heartbeat, not the beat itself. To get the truest, most accurate measure of your heart’s function, clinicians go straight to the source. This is the apical heart rate—a direct count of your heartbeats taken with a stethoscope placed over the tip (or apex) of your heart.

Why Your Apical Heart Rate Is the Truest Measure

Think of it like this: feeling your wrist (radial) pulse is like feeling the vibrations of a car engine through the frame. It gives you a general idea of what’s happening. But listening to the apical pulse is like a master mechanic putting a stethoscope directly on the engine block. You get an unfiltered, direct assessment of every single contraction.

This measurement isn’t taken just anywhere on the chest. A clinician places the stethoscope on a very specific spot called the point of maximal impulse (PMI), where the heartbeat is loudest and clearest. Listening here allows for a much deeper assessment than just counting beats. We can hear:

- Rhythm: Is the beat steady and predictable, or is it erratic with skips and flutters?

- Strength: Are the heart sounds powerful and distinct, or are they weak and muffled?

- Quality: Do you hear the clean “lub-dub” of the heart valves closing, or are there extra sounds like murmurs or gallops that might signal a problem?

The Gold Standard in Cardiac Assessment

In some cases, checking the apical heart rate isn’t just a better option—it’s the only reliable one. It’s the standard method for infants and young children, whose pulses are often so fast and faint that counting at the wrist is nearly impossible.

It’s also absolutely critical for adults with known heart conditions. For someone with an arrhythmia like atrial fibrillation, the heart might contract weakly and irregularly. Not every one of those chaotic beats is strong enough to create a palpable pulse in the wrist.

Comparing the apical rate (what you hear) to the radial rate (what you feel) allows clinicians to find a “pulse deficit.” This is a red flag that the heart is working inefficiently, with some beats too weak to push blood all the way to the extremities.

Understanding what your apical heart rate reveals is a fundamental piece of managing your cardiovascular health. It’s the kind of proactive knowledge that informs everything from a routine check-up to a critical care decision. To learn more about taking a forward-thinking approach to your cardiac health, explore our guide on what is preventive cardiology and see how it helps you stay ahead of potential issues.

How to Measure the Apical Heart Rate Correctly

Think of your heart as your body’s engine. While you can feel the vibrations through the chassis by checking a pulse at your wrist, the most accurate diagnostic comes from listening directly to the engine itself. Measuring the apical heart rate is the clinical equivalent of a master mechanic putting a stethoscope right on the engine block.

This fundamental skill offers a direct, unfiltered window into cardiac function. It requires a good stethoscope, a bit of anatomical knowledge, and careful attention to detail—but the payoff is a far more accurate reading than any peripheral pulse can provide.

First, you’ll need the right tools: a quality stethoscope with both a diaphragm (the flat, larger side) and a bell (the smaller, cup-shaped side) and a watch with a second hand. For routine heart sounds, the diaphragm is your go-to, as it’s designed to pick up the higher-pitched “lub-dub” sounds of a healthy heartbeat.

The conceptual flow is simple: a wrist pulse is a good estimate, but the apical pulse is the definitive source.

This visual shows why we go to the source. While a peripheral pulse is convenient, listening directly at the heart’s apex provides the most reliable data, eliminating any interference from the vascular system.

Locating the Point of Maximal Impulse

The secret to an accurate apical measurement is finding the point of maximal impulse (PMI). This is the precise spot on the chest where the heartbeat is loudest and clearest because it’s where the heart’s apex is closest to the chest wall.

Here’s how to find it using anatomical landmarks:

- Start at the Sternum: Find the sternal notch (the small dip at the base of the throat) and trace your finger down the center of the breastbone.

- Feel for the Ribs: Move your fingers just to the left of the sternum. You’ll feel the bony ribs and the softer spaces between them—these are the intercostal spaces.

- Count Down to Five: Carefully count down to the fifth intercostal space.

- Find the Midclavicular Line: Imagine a vertical line dropping straight down from the middle of the person’s collarbone (clavicle). The PMI is where this imaginary line crosses the fifth intercostal space.

Keep in mind that this location can shift slightly depending on a person’s age, body build, or certain medical conditions, but it’s the standard and most reliable place to start.

The Step-by-Step Measurement Process

Once you’ve pinpointed the PMI, you’re ready to take the measurement. Make sure your patient is comfortable—either sitting upright or lying down—and the room is quiet enough for you to hear clearly.

- Warm the Stethoscope: A cold stethoscope can be jarring and might even cause a temporary jump in heart rate. Briefly warm the diaphragm by rubbing it in the palm of your hand.

- Place the Diaphragm: Position the diaphragm firmly over the PMI. You should immediately hear the classic “lub-dub” of the heartbeat. Each complete “lub-dub” sound counts as one single beat.

- Count for a Full 60 Seconds: With your eyes on your watch, start counting the beats. It’s crucial to count for a full minute.

Why a full minute is non-negotiable: Taking a shortcut—like counting for 15 seconds and multiplying by four—is a recipe for missing critical information. Irregular rhythms or skipped beats often don’t reveal themselves in a short time frame. A full 60-second count is the only way to reliably detect arrhythmias and ensure clinical accuracy.

Understanding Normal Heart Rate Ranges by Age

What’s considered a “normal” heart rate isn’t a single, static number. It’s a moving target that changes dramatically throughout our lives, especially from infancy to adulthood. Think of it like a small engine versus a large one; a newborn’s tiny heart has to beat much faster to meet the body’s metabolic demands compared to a teenager’s larger, more efficient cardiovascular system.

This evolution is why context is everything when interpreting an apical heart rate. A rate that’s dangerously fast (tachycardia) for a grown adult might be perfectly healthy for a toddler. On the other hand, a strong, slow resting rate in an adolescent could signal a serious problem (bradycardia) if found in an infant.

From Infancy to Adolescence

The most significant shifts happen in the first few years. A baby’s small heart and sky-high metabolic rate demand rapid-fire pumping to get oxygen and nutrients where they need to go. As a child grows, their heart muscle gets stronger and the amount of blood pumped with each beat increases, allowing the rate to slow down while still doing its job effectively.

Because of this physiological development, the expected apical heart rate ranges vary quite a bit across different age groups. Having a clear reference is vital for both parents and clinicians, as it turns a simple number into a meaningful health indicator.

This table breaks down the expected beats per minute (BPM) for different pediatric age groups.

| Age Group | Normal Apical Heart Rate (BPM) |

|---|---|

| Preterm Infant | 120-180 |

| Newborn (0-1 month) | 100-160 |

| Infant (1-12 months) | 80-140 |

| Toddler (1-3 years) | 80-130 |

| Preschooler (3-5 years) | 80-110 |

| School-Age (6-12 years) | 70-100 |

| Adolescent (13-18 years) | 60-90 |

As you can see, the numbers are highest in the most fragile patients, like preterm infants, and gradually decrease as a child matures. You can dive deeper into the full clinical data on expected apical pulse rates for children for a more detailed review.

This age-specific context is critical. A single apical heart rate reading is almost meaningless without knowing the patient’s age. It provides the essential baseline for determining whether a heart is functioning as expected for its developmental stage.

Ultimately, this understanding helps identify potential issues early on, transforming routine measurements into powerful preventive insights.

Decoding the Apical-Radial Pulse Deficit

Think of a healthy heart as a perfectly synchronized orchestra. Every beat you hear with a stethoscope over the chest—the apical pulse—should send a corresponding pressure wave you can feel at the wrist—the radial pulse. The two counts should always match, one for one.

But what happens when the orchestra’s timing is off? This is precisely what we see with a pulse deficit, a critical clinical sign where the radial pulse count is lower than the apical heart rate. It’s a red flag that the heart isn’t pumping as efficiently as it should be.

This mismatch happens when some of the heart’s contractions are too weak to push a palpable wave of blood all the way to your peripheral arteries. The heart is beating, but not every beat has enough force to be felt at the wrist.

Uncovering the Discrepancy

Imagine a factory assembly line running smoothly. Every product that starts at the beginning makes it to the shipping dock at the end. A pulse deficit is like discovering that some products are falling off the line halfway through—they’re being produced but never reaching their destination.

This is a classic indicator of certain cardiac arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation (AFib). In AFib, the heart’s upper chambers quiver chaotically, leading to irregular and often very weak contractions. Many of these feeble beats can be heard at the apex but don’t generate enough power to create a detectable pulse at the wrist.

Identifying a pulse deficit elevates a routine vital sign check into a powerful diagnostic moment. It gives us a real-time snapshot of the heart’s mechanical efficiency, signaling that something is disrupting the effective flow of blood.

The Two-Person Measurement Technique

Because a pulse deficit requires measuring two different things at the exact same time, it’s best identified using a two-person technique. This method ensures both counts are taken over the identical 60-second period, which eliminates the guesswork and potential errors of back-to-back readings.

Here’s how clinicians perform this crucial assessment:

- Clinician One: Uses a stethoscope to find and count the apical pulse at the point of maximal impulse (PMI).

- Clinician Two: Simultaneously finds and counts the radial pulse on the patient’s wrist.

- Synchronized Count: One person gives a “start” signal, and both clinicians count the beats they hear or feel for one full minute.

- Calculate the Deficit: At the end of the minute, they compare their counts. The deficit is calculated by subtracting the radial rate from the apical rate.

For instance, if the apical rate is 110 BPM and the radial rate is only 88 BPM, the pulse deficit is 22. That number is significant—it means 22 heartbeats every minute were too weak to perfuse the body’s peripheral tissues. Finding a difference like this is a crucial step that almost always triggers further investigation, like an electrocardiogram (ECG), to pinpoint the underlying cause.

What Causes an Abnormal Apical Heart Rate

An abnormal apical heart rate can mean many things. Sometimes, it’s just your body’s temporary reaction to life—the rapid thumping after a strong espresso or a stressful meeting. That’s perfectly normal.

But a heart rate that’s consistently too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia), or simply erratic is a different story. Think of it as an instrument falling out of tune. These aren’t just numbers; they’re signals that something deeper may be disrupting your heart’s electrical system or physical structure, and they warrant a closer look.

Pathological Causes of Irregular Rhythms

When the cause isn’t just a fleeting response to daily life, we start looking at underlying conditions. The heart relies on a sophisticated electrical system to coordinate every single beat, and most persistent rhythm problems start here.

A few common culprits are behind most irregular apical readings:

- Arrhythmias: Conditions like atrial fibrillation throw the heart’s electrical signals into chaos, creating a highly erratic rhythm. This is a classic cause of a pulse deficit, where the apical rate is much higher than what you can feel at the wrist.

- Heart Failure: When the heart muscle weakens, it can’t pump blood efficiently. To compensate, it often starts beating faster, leading to a state of chronic tachycardia.

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Your heart’s electrical stability depends on a precise balance of minerals like potassium and calcium. If these levels are off, it can easily trigger an arrhythmia.

- Structural Heart Disease: Any physical problem with the heart’s valves, chambers, or muscle tissue can interfere with its ability to generate a steady, effective beat.

Getting to the bottom of these electrical disturbances is a specialized field. To understand how cardiologists diagnose and treat these complex issues, you can learn more about the world of cardiac electrophysiology and its crucial role in managing heart rhythm disorders.

Focus on Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

One very specific and serious structural problem is apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (ApHCM). In this condition, the heart muscle thickens abnormally right at the apex—the exact spot where we measure the apical pulse. This thickening makes the heart stiff, gets in the way of electrical signals, and makes it harder for the heart to fill and pump blood.

For a patient with ApHCM, an abnormal apical rate is a significant clue. Because the disease is located at the apex, this measurement offers a direct window into how the thickened muscle is affecting the heart’s overall performance.

Subtle changes in the apical rate over time can signal that a patient’s condition is worsening. In fact, a detailed analysis of 98 patients with ApHCM found that even small deviations from their baseline heart rate were correlated with their long-term prognosis. It’s a powerful reminder of how closely these measurements need to be watched. Recognizing an abnormal apical finding is the critical first step toward getting the right diagnosis and a life-saving management plan.

When Apical Findings Point to Serious Risk

While many things can cause a temporary blip in your heart rate, certain findings at the apex can be the first whisper of a serious, underlying storm. Sometimes, a routine listen with a stethoscope is all it takes to uncover clues that demand immediate and advanced medical attention.

One of the most significant concerns is a left ventricular apical aneurysm. The best way to picture this is as a dangerous, weakened bubble forming on the wall of the heart’s main pumping chamber. This isn’t just a minor flaw; it’s a structural defect that dramatically compromises the heart’s strength and can lead to life-threatening complications.

The Dangers of a Weakened Heart Wall

When an aneurysm forms at the heart’s apex, it creates a perfect storm for a major cardiac event. The weakened, bulging tissue throws a wrench into the heart’s normal electrical signaling and hobbles its ability to pump blood effectively.

This can spiral into several critical problems:

- Severe Arrhythmias: The damaged tissue can short-circuit the heart’s electrical system, triggering chaotic and potentially lethal heart rhythms.

- Blood Clots (Thrombus): Blood can become stagnant and pool in the aneurysm’s pouch, forming clots. If one of these clots breaks free, it can travel to the brain and cause a devastating stroke.

- Sudden Cardiac Death: An apical aneurysm is a major red flag for sudden cardiac arrest, which often strikes with little to no warning.

Patients with a condition called apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who develop these aneurysms face a shocking increase in risk. One study found their annual adverse event rate, including sudden death, was 10.5%. This is a world away from the typical 1-2% risk seen in uncomplicated cases. You can dig deeper into the clinical correlates of apical outpouching to see the data for yourself.

Because the stakes are so high, catching an apical aneurysm is absolutely critical. Initial clues from an abnormal apical heart rate might be the trigger that prompts a deeper look with advanced imaging, like a cardiac MRI, which can definitively confirm the diagnosis.

For patients with a confirmed high-risk aneurysm, a cardiologist will likely recommend an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Think of this device as a personal firefighter for the heart—it constantly monitors for dangerous rhythms and can deliver a shock to restore a normal beat, acting as a crucial safety net. The journey from a simple pulse check to advanced diagnostics, like those discussed after you learn about abnormal stress test results, shows how one small finding can set in motion a cascade of life-saving interventions.

Frequently Asked Questions About Apical Heart Rate

To wrap things up, let’s tackle some of the most common questions that pop up when we talk about the apical heart rate. These quick insights should help lock in the key concepts and reinforce why this measurement is so vital in a clinical setting.

Why Is the Apical Heart Rate Counted for a Full Minute?

Counting for a full 60 seconds is the undisputed gold standard for accuracy. Period. It’s the only way to get a complete and reliable picture of both the heart’s rate and its rhythm.

Shorter counts, like timing for 30 seconds and doubling it, might seem convenient, but they’re a risky shortcut. This method can easily miss intermittent problems—things like skipped beats, extra beats, or the chaotic, unpredictable patterns you see in conditions like atrial fibrillation. A full minute ensures nothing gets overlooked.

Can I Measure My Own Apical Heart Rate?

While it’s technically possible if you have a stethoscope lying around, it’s not a good idea. Accurately finding the point of maximal impulse and correctly interpreting the sounds on your own body is incredibly difficult. The angle, the pressure required—it all makes self-assessment unreliable.

For a dependable measurement, the apical pulse should always be taken by a trained healthcare professional. If your doctor wants you to monitor your heart rate at home, they will almost certainly recommend a more user-friendly method, like checking your radial (wrist) pulse or using an automated blood pressure machine.

An apical pulse measurement is a clinical skill. For at-home monitoring, consistency and ease of use are key, which is why peripheral methods are preferred for patients.

What Should I Do If I Find an Irregular Apical Heart Rate?

Discovering an irregular rhythm, a pulse deficit, or a rate that is consistently too fast or too slow is a finding that demands action. It should never be ignored.

If you’re a healthcare provider, your immediate next step is to meticulously document your findings and report them to the supervising clinician or physician for further assessment.

If you’re a patient or caregiver and you notice an irregularity, you should contact your doctor or cardiologist right away. This information is a crucial clue that can help them decide if more diagnostic work, like an electrocardiogram (ECG), is needed to investigate the underlying cause.

Finding a trusted cardiologist who understands the nuances of advanced diagnostics is essential for your long-term health. The Haute MD network provides direct access to the nation’s leading, board-certified physicians who specialize in preventive and executive cardiac care. Explore top cardiology experts in your area by visiting Haute MD website.