When you’re faced with an acute asthma exacerbation, your first few minutes of action can change the entire course of the event. The goal is simple but critical: stabilize the patient. This means rapidly reversing the bronchoconstriction that’s making it hard to breathe and simultaneously tackling the underlying inflammation fueling the attack.

It all starts with a swift but sharp assessment to figure out just how bad things are.

Every healthcare professional knows that feeling when a patient presents with a severe asthma attack. Time feels like it’s compressing, and your actions need to be precise and immediate. A structured response is non-negotiable.

This initial evaluation goes far beyond just listening for the classic wheeze. You need objective data, and you need it now, to build a clear clinical picture that will guide your treatment intensity.

Here’s what I’m looking for in those first moments:

To help clinicians quickly categorize the severity on the fly, I find a simple table can be incredibly useful.

| Parameter | Mild-Moderate Exacerbation | Severe Exacerbation | Life-Threatening Exacerbation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech | Sentences | Phrases or single words | Mute |

| Alertness | May be agitated | Usually agitated | Drowsy or confused |

| Resp. Rate | Increased | Often >30/min | Paradoxical breathing, fatigue |

| Pulse | <100-120 bpm | >120 bpm | Bradycardia, arrhythmia |

| PEF | >50% predicted/best | <50% predicted/best | <33% predicted/best |

| SpO2 (Room Air) | >92% | <92% | Cyanosis, SpO2 <90% |

| Auscultation | Wheezing | Loud wheezing | Silent chest |

This table provides a quick reference, but always trust your clinical judgment. A “silent chest” is far more ominous than loud wheezing, as it indicates dangerously low airflow.

Once you have a grasp on the severity, it’s time to act. The absolute first priority is oxygenation. Get that patient on supplemental oxygen via a nasal cannula or mask with the goal of keeping their SpO2 at or above 92%.

At the same time, you need to start aggressive bronchodilator therapy. High-dose inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs), like albuterol, are the cornerstone of treatment. I typically administer them via a nebulizer or a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer, often giving repeated doses back-to-back in that first critical hour. This provides immediate relief by relaxing the constricted airway muscles.

We often use the term “status asthmaticus”—now frequently called “severe acute asthma”—for exacerbations that just don’t respond to the initial rounds of beta-agonist therapy. These patients are essentially “stuck” in their attack, and it’s a clear sign that you need to escalate care quickly.

Here’s where a lot of older protocols fell short. Bronchodilators open the airways, but they do nothing for the fire—the inflammation—that’s causing the attack in the first place.

This is why getting systemic corticosteroids on board early is so vital. Whether oral or IV, steroids start working to reduce airway swelling and mucus production. This helps prevent the attack from dragging on or, worse, rebounding.

The entire approach to rescue therapy is shifting. For years, we relied on SABA-only rescue, but we now know that’s like fighting a fire without water. In the U.S. alone, there are an estimated 9 million asthma exacerbations among adults each year, leading to over 716,000 emergency room visits. We have to do better.

Current guidelines are moving toward an anti-inflammatory rescue strategy. This often means using a combination inhaler with a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and formoterol. This dual-action approach tackles both the bronchospasm and the inflammation right from the start, leading to much better outcomes. You can learn more about this important shift by reading these insights on asthma management on statnews.com.

Once you’ve completed your initial assessment and have supportive care like oxygen running, the game plan shifts to a powerful trio of medications. These are the workhorses that reverse bronchospasm and attack the underlying inflammation head-on. Getting these drugs administered swiftly and correctly isn’t just a box to check; it’s the critical step that stops a severe attack from spiraling into a life-threatening emergency.

Think of it like this: the airways are a clogged pipe. You need something to blast it open right now, but you also need to shut off whatever is causing the blockage in the first place. This two-pronged approach is the foundation of everything we do.

The first line of defense is always aggressive bronchodilation with short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs). Albuterol is our go-to, and it works fast to relax the smooth muscle choking the airways, giving the patient almost immediate relief from that awful wheezing and shortness of breath.

For a patient in moderate to severe distress, a single puff from their home inhaler is not going to cut it. We need to hit them with repeated, high-dose treatments.

When a patient is really struggling, we often add ipratropium bromide, an anticholinergic agent, right into the albuterol nebulizer. The combination is synergistic—they block different pathways that lead to bronchoconstriction, giving you more bang for your buck. A standard dose is 0.5 mg mixed with the albuterol for the first three treatments.

For example, a patient who arrives with audible wheezing and a PEF at 40% of their personal best would get three back-to-back albuterol/ipratropium nebulizers. If their work of breathing eases and their PEF climbs over 70% after that first hour, we can start spacing out the treatments. If not, they might need continuous nebulization, which is a big red flag that we’re dealing with a stubborn, severe attack.

While SABAs provide immediate, life-saving relief, they do absolutely nothing for the root cause of the exacerbation: airway inflammation. That’s the job of systemic corticosteroids. These are non-negotiable for reducing swelling, cutting down mucus production, and preventing a rebound of symptoms once the bronchodilators wear off.

Getting steroids on board early is one of the most important things you can do for anyone having a moderate to severe attack. The choice between oral and intravenous (IV) really just comes down to the patient’s condition.

| Route of Administration | Typical Medication & Dose (Adult) | When to Use It |

|---|---|---|

| Oral (PO) | Prednisone, 40-60 mg daily | For patients who aren’t in extreme distress, can swallow safely, and aren’t vomiting. Oral steroids are absorbed really well and are just as effective as IV for most people. |

| Intravenous (IV) | Methylprednisolone, 40-80 mg | Reserved for patients in severe respiratory distress, those who can’t take anything orally, or if you’re worried about GI absorption. |

The key thing to remember is that steroids aren’t instant. Their benefits don’t really kick in for 4 to 6 hours. This is precisely why they have to be given alongside the fast-acting bronchodilators, not instead of them. For a patient stable enough for discharge, we typically send them home with a 5- to 7-day “burst” of oral prednisone, which usually doesn’t need to be tapered.

Let’s put it all together. Imagine a 35-year-old patient who walks in speaking in three-word phrases, with an oxygen saturation of 91%. The immediate pharmacological game plan looks like this:

This multi-pronged attack ensures we are aggressively treating both the symptoms and the underlying pathology from the second they arrive. By combining fast-acting bronchodilators with powerful anti-inflammatory agents, we give the patient the best possible chance for a quick and lasting recovery. The goal isn’t just to stabilize them for the next hour, but to break the cycle of inflammation and keep them from bouncing right back to the ED.

Initial treatment for an acute asthma flare-up is all about hitting it hard and fast. But what you do next is just as important. That first hour is a critical observation period that dictates your entire game plan. Managing an asthma exacerbation effectively isn’t a static protocol; it’s a dynamic dance of continuous evaluation and adjustment.

So, how do you know if your interventions are actually working? You need to systematically re-evaluate the same key markers you used in your initial assessment. This constant feedback loop is the only way to know if the patient is turning a corner or sliding toward respiratory failure.

After that first hour of intensive treatment—usually back-to-back bronchodilators and systemic steroids—it’s time for a formal reassessment. I’m not just looking for the patient to say they feel better; I need to see clear, objective signs of improvement. We’re talking measurable progress.

These are the core parameters I’m tracking:

The one-hour mark is a crucial decision point. If a patient shows solid improvement across these areas, you’re on the right track. If they are static or, worse, deteriorating, it’s a clear signal that your first-line therapies aren’t cutting it. You have to escalate care, and you have to do it now.

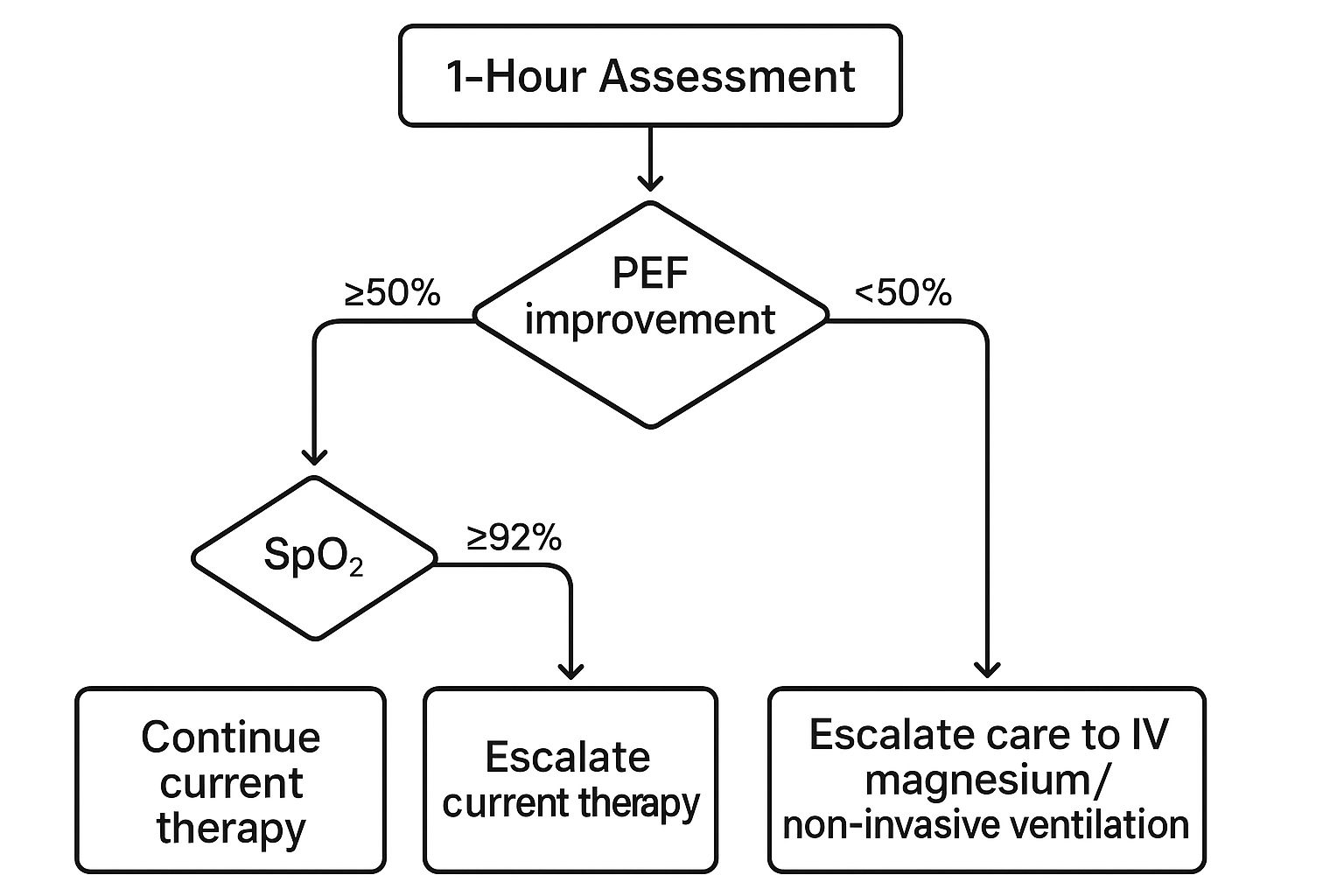

The decision tree below gives you a great visual for this critical one-hour assessment, showing how PEF and SpO2 levels should guide your next steps.

This guide really hammers home the point: if a patient’s PEF remains below 50% or their oxygen saturation is still low after an hour, it’s time to move beyond the standard playbook.

When a patient fails to respond to that initial barrage, you’re now managing severe acute asthma, sometimes called status asthmaticus. This is a medical emergency. The patient’s condition is unyielding, and you must introduce more powerful, second-line interventions to prevent them from progressing to full-blown respiratory arrest.

Here are the key escalation therapies to have ready:

Global data really underscores how challenging these events are to manage. Uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma affects up to 49% of patients in the US. In some parts of Europe, that number skyrockets, with nearly all such patients (96.4%) experiencing at least one exacerbation per year. This highlights the global burden and the critical need for effective escalation strategies. You can dive deeper into the global asthma statistics on ciplamed.com to really grasp the scope of this problem.

Recognizing when to escalate is a non-negotiable clinical skill. This table outlines the key triggers that should make you think about advanced therapies or an ICU consult.

| Clinical Indicator | Threshold for Escalation | Potential Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| PEF | Fails to improve or remains <50% post-treatment | IV Magnesium, Consider NIV |

| Work of Breathing | Persistent accessory muscle use, inability to speak | Non-Invasive Ventilation (BiPAP/CPAP) |

| Mental Status | Drowsiness, confusion, agitation | Prepare for intubation, ICU admission |

| SpO2 | <92% despite high-flow supplemental O2 | NIV, Mechanical Ventilation |

| PCO2 (ABG) | Normalizing or rising PCO2 (>42 mmHg) | Immediate consideration for intubation/ICU |

| Clinical Gestalt | Patient appears exhausted or “tiring out” | Escalate care immediately (NIV/Intubation) |

Seeing any of these signs, especially a combination of them, means the patient is on a dangerous trajectory. The time for waiting is over.

Let’s put this into practice. Imagine a 45-year-old patient who came in with a PEF of 40%. After an hour of continuous albuterol, ipratropium, and IV methylprednisolone, her PEF is still only 45%. She’s tachypneic at 32 breaths per minute, her SpO2 is struggling at 91% on 4 liters of oxygen, and she just looks exhausted.

This is a classic picture of a poor response. Your next steps should be automatic:

By recognizing the red flags of a poor response and escalating care promptly with therapies like magnesium and NIV, you provide a critical bridge to recovery. More often than not, it’s what keeps them off a ventilator.

The immediate crisis might be over, but our work is far from done. A thoughtful and thorough discharge plan is the single most important factor in preventing that patient from landing right back in the emergency department in a few days or weeks. This isn’t just about handing over prescriptions; it’s about turning a moment of crisis into a powerful opportunity for education and long-term empowerment.

Our goal is to bridge the gap between acute care and chronic management. We need to ensure the patient leaves not just stabilized, but also better equipped to handle their asthma on their own. This transition is where so many patients fall through the cracks, leading to a frustrating and dangerous cycle of repeated attacks.

Before anyone goes home, they have to meet specific clinical criteria. This isn’t a judgment call; it’s a data-driven decision. The patient needs to be stable for at least an hour, showing a sustained response to our treatment.

Here are the non-negotiables:

Once we’ve confirmed they’re stable, the focus shifts to arming them with the tools and knowledge they’ll need at home. This means getting the right medications into their hands and, crucially, making sure they understand exactly how to use them.

Sending a patient home after an attack without the proper medications is a setup for failure. The standard of care is a two-pronged approach to manage the lingering inflammation and prepare for future flare-ups.

First, every patient who had a moderate to severe exacerbation needs a short course of oral corticosteroids. A typical prescription is prednisone (40-60 mg daily for 5-7 days). This steroid “burst” is absolutely vital for stamping out the underlying airway inflammation and preventing a rapid relapse.

Second, we need to modernize their inhaler strategy. The old habit of sending patients home with only a SABA (albuterol) rescue inhaler is dangerously outdated. Current guidelines strongly favor a combination inhaler, like budesonide/formoterol, which acts as both a maintenance and a reliever therapy. This ensures they get a dose of anti-inflammatory medication with every single rescue puff.

Key Takeaway: The practice of discharging a patient with a SABA inhaler alone should be a thing of the past. A combination ICS/LABA inhaler provides both immediate relief and tackles the underlying inflammation, drastically cutting the risk of another attack.

Medications are only as good as the technique used to take them. One of the most common reasons for treatment failure is simply poor inhaler use. Before they walk out the door, you have to watch the patient use their inhaler and spacer, providing direct feedback and correction on the spot. It’s a simple step that can make a world of difference.

This education must also include a written Asthma Action Plan. This personalized document is their roadmap, detailing:

This plan removes the guesswork and empowers the patient to act decisively at the first sign of trouble. The quality of this discharge phase is critical, yet the data shows significant gaps in care. Research reveals that only 18.2% of emergency department reports contain all recommended discharge information. Shockingly, systemic corticosteroids were prescribed in only 46.9% of cases, despite their proven ability to prevent a recurrence.

Finally, the emergency visit should never be the end of the story. A crucial part of the discharge plan is scheduling timely follow-up care. The patient needs an appointment with their primary care physician or an allergy and immunology specialist within a week. You can learn more about how these specialists create long-term strategies in our overview of allergy and immunology care.

This follow-up serves several key purposes. It’s a chance to review the asthma action plan, assess potential triggers like allergies or environmental exposures, and fine-tune their long-term controller medication. It reinforces the message that asthma is a chronic condition requiring proactive management, not just reactive treatment during a crisis. By closing this loop, you help transition the patient back into a stable, well-managed state, significantly reducing their risk of another severe attack.

The standard protocol for a severe asthma attack is a solid starting point, but let’s be honest—medicine in the real world is never that simple. The textbook patient doesn’t walk through the door very often. You’re constantly dealing with unique situations like pregnancy, very young patients, or people with a laundry list of other health problems.

These factors can completely change your game plan. What works for a healthy 30-year-old might be dangerous for a 70-year-old with heart failure. This is where clinical judgment and experience come into play, moving beyond a rigid algorithm to tailor treatment for the actual person in front of you.

When a pregnant patient is having an asthma attack, you’re treating two people at once, and the stakes are incredibly high. The guiding principle is simple but critical: an uncontrolled asthma attack is far more dangerous to the fetus than the medications we use to treat it.

When the mother can’t breathe, the baby can’t get oxygen. Maternal hypoxia quickly leads to fetal hypoxia, which can have devastating consequences. Your goal has to be aggressive, rapid treatment to get her oxygen levels back to normal as fast as humanly possible.

The bottom line is to treat pregnant patients just as aggressively as you would anyone else—if not more so. Under-treatment is the real danger here. Poor oxygen control for mom can seriously impact fetal development.

Children aren’t just little adults. Their anatomy, physiology, and how they react to medications are all different, so you have to adjust your approach. Everything comes down to weight-based dosing to avoid giving too little medication (which won’t work) or too much (which can be toxic).

The way you deliver the medication is also a huge practical consideration. An older kid might handle a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a spacer just fine. But for a toddler or any child in severe distress, a nebulizer is often the better choice. The continuous flow of medicated mist is less scary and ensures they get the medicine even if their breathing is fast and shallow.

Remember to bring the parents or caregivers into the process. Explaining what’s happening and how they can help keep their child calm makes a huge difference. A terrified, crying child has a much higher work of breathing, which just makes the whole situation worse.

Pre-existing health conditions can throw a major wrench in your plans. This is especially true for patients with cardiovascular disease, like congestive heart failure (CHF) or a history of heart attacks.

High doses of beta-agonists like albuterol can cause a rapid heart rate (tachycardia) and tremors. While that’s just an uncomfortable side effect for most people, it can put a dangerous amount of strain on a weak heart. You still have to use the medication—it’s lifesaving—but you must monitor them like a hawk for any signs of trouble, like chest pain or changes on the EKG.

In these complicated scenarios, having a personalized allergy and asthma treatment plan from a specialist is invaluable. Knowing the patient’s full medical history lets you anticipate these problems instead of just reacting to them in the middle of a crisis.

Finally, while you’re focused on the immediate emergency, don’t forget to play detective. Figuring out what triggered the attack is key to preventing the next one. One of the most common culprits, especially for severe flare-ups, is a respiratory infection—usually a virus.

Be on the lookout for signs of infection like a fever, discolored sputum, or sinus pain. While antibiotics aren’t a routine part of asthma treatment (since most triggers are viral), you absolutely need to identify and treat a co-existing bacterial infection like pneumonia or sinusitis. Looking at the whole picture ensures you’re not just putting out the fire but also dealing with what started it.

Even with a solid protocol, managing an acute asthma attack is a high-pressure situation. Certain questions always seem to pop up, and having clear, evidence-based answers ready is key to providing the best care. Let’s walk through some of the most common clinical dilemmas.

It’s a common question, especially when a patient is coughing up phlegm. The short answer? No.

The routine use of antibiotics in acute asthma is not recommended. The overwhelming majority of these exacerbations are kicked off by viruses, not bacteria. Giving an antibiotic that won’t work just exposes the patient to side effects and fuels the larger problem of antibiotic resistance.

Of course, there are exceptions. You should absolutely start antibiotics if you have clear, compelling evidence of a bacterial infection happening at the same time. Think things like:

Without those strong indicators, the focus should stay exactly where it belongs: on powerful bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory corticosteroids.

Sending a patient home with a short course of oral steroids is a critical part of preventing a rebound attack. A standard “steroid burst” is the cornerstone of a safe discharge plan.

Typically, this means a 5 to 7-day course of a medication like prednisone. This is usually just the right amount of time to knock down the underlying airway inflammation and stop symptoms from roaring back.

One of the best things about this short duration is that it does not require a gradual taper. A 5-day course isn’t long enough to suppress the body’s own steroid production, so patients can simply stop taking the pills after the last dose. This makes instructions much simpler and helps people actually finish the full course.

A classic mistake I see is patients stopping their steroids as soon as they start feeling better. We have to be crystal clear in our discharge counseling: “Even if you feel 100% back to normal by day two, you must finish the entire 5-day course.” This is non-negotiable for preventing a relapse.

An ER visit or hospitalization for asthma is a huge red flag. It’s a sign that a patient’s day-to-day asthma management is failing. While every patient needs a follow-up with their primary care doctor, some absolutely need to be escalated to a specialist—either a pulmonologist or an allergist/immunologist.

So, who needs that referral? I strongly recommend it for patients who have:

Getting these high-risk individuals into a specialist’s care can open the door to advanced therapies, more precise trigger identification, and a long-term strategy that can finally break the cycle of crisis.

At Haute MD, we connect discerning patients with the nation’s leading, board-certified physicians who specialize in complex conditions like severe asthma. Find a trusted expert near you and gain access to premium, outcome-driven care. https://www.hauteliving.com/hautemd